Blog

History

Workboats: The Peapod “rows quick and tows slick"

When you’re working the tidal zone around rocks, it helps to have a bow on each end. A nice historical brief from Soundings’ Carly Sisson:

A Downeast Peapod by Sparkman & Stephens

by Carly Sisson

Photography by Denis Dowling

In the mid-19th century, Maine’s lobstering industry was in its infancy. Lobster, once common cuisine for the poor and even picked from the beach by prisoners for their meals, did not evolve into a delicacy until the early 1800s. By the 1840s, Maine had established its first commercial lobster fishery. With the birth of this new industry came the need for vessels capable of harvesting the crustaceans from Maine’s waters, as picking them from the shore could no longer meet the growing demand. Thus, the state’s iconic workboats were born. One of those boats was the peapod.

Using cold-molded construction, Sparkman & Stephens simply glues and clamps strip planking to the frames, eliminating the need for rivets and drastically reducing the boat’s weight.

Peapods were developed around 1870 as nearshore lobstering and fishing boats. One common theory is that the plank-on-frame rowboats first originated in Owls Head on Penobscot Bay, where they were called double-enders, with peapod becoming the more common name on the mainland.

Peapods were usually 13.5 to 15 feet overall (though some of the early workboats were built up to 20 feet), with cedar planks and oak frames. They were either clinker-built or carvel-planked, and they featured a shallow draft and symmetrical hull, making them well-suited for the early lobstering days, when lobstermen set their traps close to the rocks rather than out in the channels.

“The whole reason for the design is that when you’re lobstering, you’re rowing in and out of rocky crevices. There’s not enough room to rotate the boat 180 degrees to get back out,” says Cipperly Good, curator at the Penobscot Marine Museum. “With a double-ender, you can row as easily forward and backwards. You just turn yourself around and row the other direction.”

Top: A craftsman mills strakes for the hull layup.

The boats were sturdy and stable, allowing lobstermen to haul traps over the sides without capsizing. Many of the early peapods could only be rowed standing up, so the rower could see buoys more easily and work in and out of ledges, but other working designs featured one station for standing and rowing and another for sitting and pulling traps.

Functional yet simple, peapods had wide appeal in the state. “They were something people could build themselves,” says Good. But they were not all homemade. A few notable builders developed their own peapod designs, including Captain Havilah Hawkins Sr., who started producing his 13.5-foot model in 1954 out of an old mill in Brooksville. He built 47 peapods over 10 years, and in 1964, Jimmy Steele took over Hawkins’ design.

“He had this feeling that it would make a good tender for, as they say in Maine, people from away,” says Donald Tofias, owner of Sparkman & Stephens and Steele’s peapod design. Steele built an estimated 178 peapods between 1964 and 2007, modifying Hawkins’ design over the years by adding more sheer and hollow in the bow. He sold them directly to customers out of his shop in Brooklin and named his business the Downeast Peapod company.

Steele’s Downeast Peapods came in three models. The Chevrolet was the all-painted version. Next was the Cadillac, which had a varnished sheer and seats. The Rolls was his ultimate boat, featuring an all-varnished interior.

The new cold-molded peapod features locust frames and cherry stringers, as well as 75 percent fewer ribs.

“Jimmy found a way to mass produce them,” says Good. The forward-thinking builder was able to meet demand by mechanizing the build process. He attached a shoe to a pump that ran the pneumonic devices in his shop, so he could simply turn on the pump to continuously run the cutters, rivet gun and other tools, expediting construction. On average, he built between three and five peapods per year, with peak annual production hitting as many as 12.

Peapods transitioned from lobster boats to recreational tenders when the lobstering industry became more commercialized, necessitating more traps and larger vessels. The rowboats easily found a new job. Maine’s famous Feeder Races from Castine to Camden and Camden to Brooklin require sailboats to tow a dinghy, and the Downeast Peapod became one of the tenders of choice.

“[Maine writer] Mimi Steadman came up with the slogan that the Downeast Peapod rows quick and tows slick,” says Tofias. “There’s hardly any wetted surface, so you’re not dragging a lot of boat through the water.”

Tofias can attest to this firsthand. Owner of vintage sailing yachts (including a Concordia yawl, Herreshoff S-Boat and W-76 sloop), founder of the W-Class Yacht Company and lifelong sail racer himself, he uses his original Jimmy Steele Downeast Peapod, Ponytail, as a tender on his own boats.

Tofias purchased the Downeast Peapod company from Steele in 2007 and started building boats with Steve White, president of Brooklin Boat Yard, out of Steele’s original shop, as well as at the Landing School and more recently in Bristol, Rhode Island. He then purchased Sparkman & Stephens in 2018. Today, he is reimagining the traditional design.

In the original peapod design, the planking was riveted to the frames, which made the little boats quite heavy, weighing upwards of 200 pounds. There was also no way to attractively cover the rivets on the outside of the hull, and that detracted from the boats’ natural beauty. Tofias had an idea that would correct both of these issues.

“We decided to scan my Downeast Peapod and then build cold-molded boats that were exactly the same shape,” he says. “With cold-molded wood, you don’t need to have rivets; you just glue and clamp the strip planking to the frame.” The method also allowed them to eliminate 75 percent of the ribs. Sparkman & Stephens has finished building the first cold-molded peapod, and construction is underway on the second. The new model weighs less than half of the plank-on-frame boat, making it easier to handle, lighter to bring up on deck, and less strenuous on the jib or spinnaker halyard. It is 13’8” long with a 4’8” beam and is large enough to seat four adults.

The strip-planked construction is reinforced wtih fiberglass and features locust frames and cherry stringers, as well as cherry seats and floorboards. The boat will also have optional gear, including extra oarlocks, an extra rowing station, standup oarlocks (like on the early workboats), lifting rings and a gunwale guard. Tofias is confident that Sparkman & Stephens will be able to build up to two dozen peapods each year.

Unlike Steele, Sparkman & Stephens will likely only be selling bright peapods sealed with clear epoxy. “Then we will allow owners to paint them or continue to build up layers of varnish or clear coat, but my preference would be to leave it all bright,” says Tofias. “I think it’s incredibly attractive to have it all varnished or clear-coated, and there are of course no rivets. I love natural wood; I always have.”

The days of hauling lobster traps over the side of rowboats may be long past, but peapods have permanently embedded themselves in Maine’s maritime culture, and Sparkman & Stephens’ Downeast Peapods are sure to attract even more loyal enthusiasts when they gleam in regattas along the coast. But boaters do not need to own a wooden yawl to enjoy this classic design; they make great recreational family vessels as well.

The first cold-molded Downeast Peapod

“Kids can learn teamwork and how to row together,” says Tofias, whether they are each taking one main oar in the middle, or the older kid is handling the main oars while the younger takes the optional smaller oars in the bow. “We encourage grandparents to buy two of them, because they’ll get to a certain age and want their own boat.”

The iconic rowboats have discovered a new recreational purpose that keeps their history alive while introducing new generations to their sea-kindly design. And with Sparkman & Stephens’ new construction method, they will not only look even sharper, but handle more easily as well. “There are a lot of imitators,” says Tofias, “but there is only one Downeast Peapod.”

This article was originally published in the June 2021 issue of Soundings.

Weather

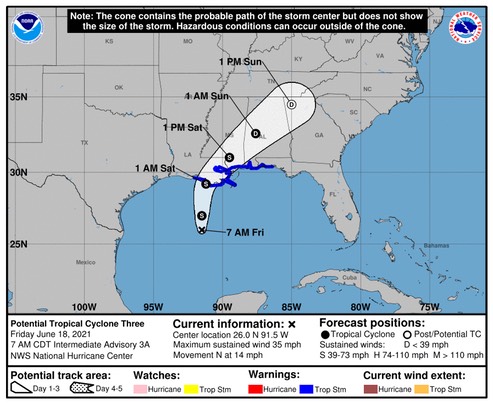

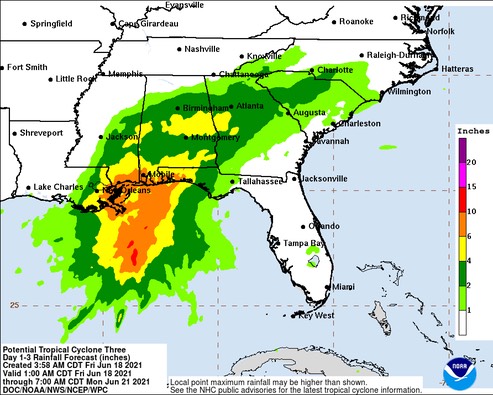

Number “Three", a Dunker?

No named status yet, but 'Potential Claudette' is continuing on its path toward the Gulf Coast.

Best keep the ‘oilies’ handy.

/fl

Weather

2021 Tropical Storm Season

Well, here we are already; a brand new “Hurricane Season.”

Ana

Bill

Claudette

Danny

Elsa

Fred

Grace

Henri

Ida

Julian

Kate

Larry

Mindy

Nicholas

Odette

Peter

Rose

Sam

Teresa

Victor

Wanda

As of this writing, Ana and Bill have already developed in the North Atlantic and present no threat to the Gulf Coast. However, we are watching “Invest 92” near Campeche Bay. Thunderstorms seem to be the biggest threat at the moment.

Welcome to summer on the Emerald Coast!

/fl

Water Safety

Dealing with Unseen Hazards

Usually, when we read a story that begins “it was a dark and stormy night,” we prepare ourselves for some kind of unfolding tragedy. But, in real life, many tragedies begin with the words found at the beginning of this story by Carly Sisson at Soundings; ”It was just a normal evening on the water.”

Seven-Year-Old Boy Swims an Hour to Save Family

Thanks to divine grace, this one has a happy ending, but it could have easily ended the other way—as a lot of them do.

‘Invisible' current, whether it be from an unseen tractive force such as tidal current, or gravitational such as a river. can be deadly if not treated with respect. It’s difficult to give proper respect to something that you can’t see and don’t know exists.

Seven-year-old Chase Poust knows! And, hopefully he will have a good long life to tell others about it.

/fl