Reminiscing Ocean Station duty—and why we were there.

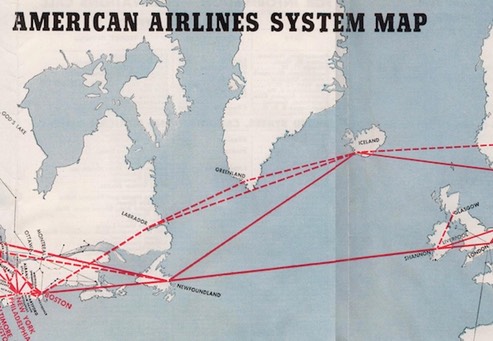

The following series of recently produced video’s re-creates the not-too-distant era of commercial aviation when trans continental air travel was a true adventure.

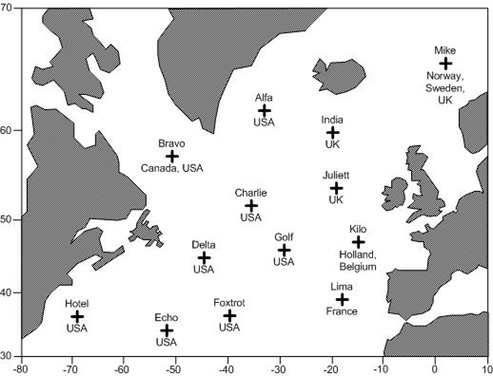

My duty in the United States Coast Guard included crewing aboard a USCG Cutter serving as an Ocean Station Vessel in the North Atlantic ocean. During the time that I was aboard, we manned Ocean Station’s “Bravo” and “Charlie.” The duty involved being “on station” (as close to the center of a 210 mile square that weather would allow) for a period of 21 days at a time, plus travel time to and from our home port of Norfolk, VA, followed by “shore time” which included repair and replenishment. Winter in the North Atlantic can be pretty demanding on equipment, so we usually had plenty of repair work to do in port.

Take a brief journey back in time...

The following photo of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Chincoteague (W-375) was taken in 1964 while I was aboard. The tripod mast nearest the stern supported our air-search radar antenna. The radar screens, VHF/UHF radio phones, plotting displays, and most of the equipment used for providing “flight services” to the airlines and commercial aviation were located in the Combat Information Center (CIC) which was located between the forward mast (the one with the flags), and the Bridge (located behind the row of round portholes.) A lively place in rough weather; this was before the days of automatic electronic displays; we calculated all speeds with a circular slide-rule, and plotted distances and positions with a grease pencil; there were days when we worked the aircraft with one hand while holding on with the other!

A brief ship’s history can be found here.

Chart showing then-existent North Atlantic Ocean Station Location’s:

Back in the 1960’s, Ocean Station “Bravo”, located at 56.5°N-51.0°W, was roughly the “point of no return” for aircraft traveling between Newfoundland and Greenland. We were there to assist anyone who might be having trouble, be it in the air or on the water. In addition to reporting and tracking icebergs for the safety of surface ships, we served as a floating flight-service station for trans Atlantic aircraft carrying passengers, cargo, and airmail.

Piston engined, non-pressurized, aircraft, such as the DC-3 (shown in Pan American World Airways “Clipper” colors) in this series of video’s are limited in their maximum altitude, in order for the engines to function (breathe) properly, and for the people on-board to be able to breathe without oxygen masks. This means that those types of aircraft cannot fly high enough to get over the weather, and must fly around any storms that they encounter in their path. That was one of our jobs; helping them avoid adverse wind and weather conditions. The air space over the North Atlantic ocean between Newfoundland and Greenland is controlled by Gander Oceanic Air Control (OAC) at Gander, Newfoundland, and all trans-oceanic flights were required to carry a High Frequency (HF) radio, in addition to the VHF radio that they use to communicate with airport towers. Even then, “radio relay” was common between aircraft—as seen demonstrated in the video.

With the exception of emergency rescue operations, our primary routine on Ocean Station was to track all aircraft that appeared on our radar, contact each flight, copy their flight data (critical progress) information, and provide course and speed information to the flight crew—along with the latest North Atlantic weather; in addition we could relay radio traffic between Gander OAC and any aircraft flying over our Ocean Station. It was common for us to get flight-level change requests due to unfavorable winds at various altitudes; these requests were received from the flight crews and relayed to Gander OAC via HF—upon approval by Gander, the clearance was relayed to the requesting flight by VHF. The process sounds unwieldy and cumbersome by todays standards, but it was state-of-the-art in the early 1960’s. Since the DC-3 aircraft used in this video has been retrofitted with more modern communications gear, they were able to get an “HF waiver” for their 1,000 mile over-water leg to Narsarssuak, Greenland and beyond to Prestwick, Scotland.

I worked four-hour watches in the Combat Information Center (CIC) tracking aircraft and copying flight data. The traffic was light by today’s standards, but hardly any 4-hour watch went by that I didn’t talk to one or more “Clipper” crews amongst the variety of other airlines. At the time, most of the airline aircraft were pressurized, with either supercharged radial or jet engines, and had more altitude options than the old DC-3 in these video’s—but there were a few just like this one.

The year 1977 saw the last of the U.S. Coast Guard Ocean Station Vessel’s, but these video’s provide a taste of the old days—what it was like for early to mid-twentieth century flight crews flying the old Ocean Station routes across the Atlantic, and why we sat out there helping them.

Semper Paratus!

/fl

UPDATE 02-25-2021: This has nothing to do with the subject matter of the above story, but it turns out that one of the “pilots” in this story received his DC-3 type rating from Dan Gryder, and the subject in question was later involved in some questionable activity; you can see more details regarding that at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J10p7yzvEw.

/fl